by accdWebMaster | Dec 13, 2021 | Creative Economy, Diversity

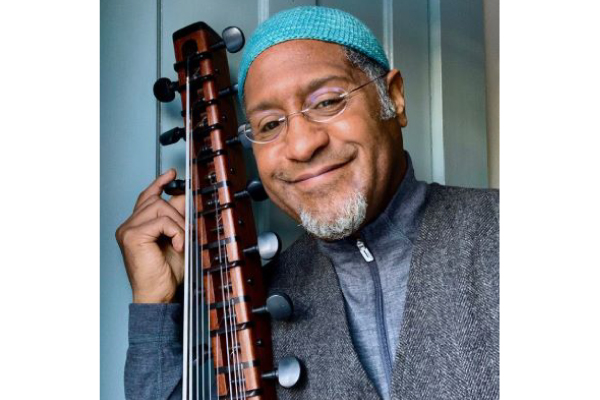

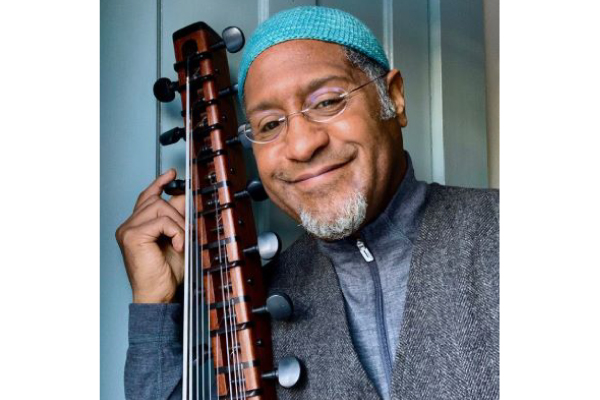

John has worked in fields as disparate as blacksmithing, glassblowing, sculpture, and dance. However he is quick to assert that all of these making activities are, for him, explorations of the same fundamental questions about matter and consciousness. He currently works primarily as a musician, instrument builder, and educator who performs internationally and teaches both kora (West African harp) and traditional West African drumming from his home base in Brattleboro.

John shared his thoughts about being a Vermont artist.

How has living as an artist in Vermont affected your creative process?

I first came to Vermont to attend The Putney School in 1982. This move from New York City to the Green Mountain State fostered and transformed my creative processes in so many essential ways! I learned blacksmithing . . . made an ax . . . and built a log cabin in which I lived until I was graduated in 1984. Though I didn’t realize it until my sophomore year in college, it was the process of building and living in the cabin in the woods that, in the most important ways, showed me that I was a sculptor and not a painter. During my days at The Putney School and since settling in Vermont after graduate school, I have found the state’s natural beauty to be deeply grounding and at once restful and inspiring.

What is something about your art that has changed over time?

Vermont’s alternately liberal and cantankerously conservative culture has been fertile ground on which to cultivate the more recent transformation from sculptor to instrument builder and musician. In many ways, I feel more connected to my community through my work as a musician than I did through my work as a sculptor. While building sculpture nourished my intellect and curiosity about the nature of the physical universe, making music has grown my compassion and sensitivity to the nonmaterial world.

What is your vision for the next several years?

In the next several years I intend to keep spreading love through music! I would like to play more public events like concerts to compliment the private events like the weddings and parties that, presently, constitute the bulk of my work. I would like to play more with other people. Living in a small town makes it challenging to find other musicians with whom to collaborate but I’m always on the lookout for the right person or people. I would also like to do more teaching again (classes and private lessons) of the kora and traditional West African drumming.

Visit John’s website.

Peruse John’s CDs here.

The “I am a Vermont Artist” series explores how artists’ creative expressions reflect their experiences of ethnicity, gender identity, religion, disability, or age. Covering all artistic disciplines, and a range of backgrounds—from New Americans to the state’s first residents—we hope to amplify voices that deepen our understanding of what it means to be a Vermont artist. This story by the Vermont Arts Council originally appeared at https://www.vermontartscouncil.org/blog/i-am-a-vermont-artist-john-hughes/

by accdWebMaster | Dec 7, 2021 | Creative Economy, Diversity, Meet Your Neighbors

Healing is as much an art as a science. It often requires sound, movement, story, and that other creative mode, community. For this kind of healing you can turn to Amber Arnold of Brattleboro, a practitioner of cultural somatics, a discipline her mentor describes as “how bodies move, breathe, think, feel, and know themselves within a culture.”

Amber is the co-organizer of the Susu Healing Collective, a botanica and community organization that offers herbal medicines and educational programs for “all people who are ready and willing to begin or continue the path of transformation through accountability, connection, and spiritual practice.” Since starting in the summer of 2019, the collective’s work has taken many forms, from leading a crowd of demonstrators in a self-soothing hum to echo that of enslaved Africans arriving on colonial America’s shores, to workshops that bring together BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color) and allies to reckon with patterns of trauma and oppression. In all instances, Amber’s work shows us how our bodies are direct lines to our ancestors, to stories of pain and healing that can unlock the world we wish to see.

Amber shared her thoughts about being a Vermont artist.

How has living as an artist in Vermont affected your creative process?

Living as an artist in Vermont has affected my creative process in many ways. Vermont has this energy that is so unique to this place, its something I’ve never experienced before (and I’ve lived in many places). There’s this constant expansion and contraction of “progressive liberal” racism to connection with room and the desire of many people for expansion, creativity and dreaming. It’s like people here are so ready to transform culture, and they’re just waiting for the visionaries, the dreamers, the ones with the ancestors’ sweetness dripping off their lips to guide them to what that could look like. The people here are so ready and willing to walk in a new way of being, they just really need people like us to see what it looks like, to be curious about it, and to give them little chances to touch into it.

Vermont is a place where I feel safe and unsafe, where I feel held and unheld, where I feel connection and disconnection, where I feel comfort and discomfort. It has played a big role in lighting the fire in my heart for bringing change and liberation. It has in many ways helped me to develop my sense of place, and the ways in which I view the world and all of my art and creative culture building is based in my deep reverence and connection to this place and the people who call Vermont home.

What is something about your art that has changed over time?

E v e r y t h i n g. Stagnation is what keeps the water from flowing. As a young person my art started as a reflection of the way in which I viewed the world and where I felt I belonged. Most of my art consisted of poetry, writing, and drawing, and it mostly focused on the areas where I felt helpless, the way that white supremacy and trauma infiltrated my boundaries and left me gasping for air, the ways in which the system and the people working within it failed me. It centered my harm and the ways the white nonprofits and people would benefit and increase their admin budgets because of the suffering of me and my people.

My art has changed just as I have, though the systems and structures still show up in the same way. My art has increased my capacity to move beyond the binaries, the boxes, the identities that American culture places us in to keep us separate. My art has transformed into visions and dreams of the ancestors, the generations to come, and the future—in the present.

Now I create living art, I dream of liberation and what that would look and feel like, and then I create living opportunities to experience and explore it in real time. My art has changed into everything that I do and all the ways I engage in commUNITY. It has informed the way I live, breathe, move, and thrive in Vermont and the ways in which I see our commUNITY and people having so many opportunities to go beyond survival.

What is your vision for the next several years?

My vision for the next several years is to create the culture here in Vermont that my ancestors dreamed of when they braided seeds in their children’s hair before they were forced to board transatlantic slave ships being sent to a world they didn’t know. To make spaces where housing and food are considered birth rights that we access freely and where working is something we do because it brings us joy and is not tied to our survival. I vision building creative opportunities for Vermonters to start exploring the ways we can move through white-bodied supremacy and into remembering the wisdom, rituals, healing, and gifts that our ancestors left for us. Ways for us to heal from the oppression that our culture has placed on the shoulders of all of us in different ways to divide and conquer, and to move into building cultures of liberation where our needs are more than met, where we can be in deep relationship with each other and the land, where our visions and dreams can freely flow, and where we can begin to do real radical work—the work we can’t do yet because we’ve been too busy fighting for our basic rights like food, shelter, being able to just be Black, and seeing joy as central to our existence.

Once we have access to life, we can really start to get radical and create a culture that centers joy, connection, safety, and where we can really start creating the things that bring healing to all of us. I vision creating spaces for the voices of the people most oppressed by this system to be their own storytellers, to share their stories, make their art, and offer their gifts to the world in a way that brings them joy and connection and is not yoked to the building and success of white nonprofits getting rich off our labor and our stories. I vision offering creative educational programs to the folx in Vermont who are interested in being part of building a culture that frees us from capitalism, political control, and white supremacy culture.

Visit the Susu Healing Collective’s website.

Learn about Susu’s BIPOC Land and Food Sovereignty Fund.

Read The Commons‘ story about Amber and cultural somatics.

Read about Susu’s contribution to recent social justice demonstrations in Brattleboro.

Amber Arnold is a manifester of abundance, community, and self-love as acts of collective liberation, resistance and reciprocity. She is deeply rooted in her vision of healing through community and everyday magic hiding in plain sight. She creates spaces that calm the nervous system, invite curiosity, and allow for abundance, deep connection, and co-regulation. Amber follows the knowledge, wisdom, and guidance of her ancestors who through pain, liberation, and resilience paved the way for her to offer seeds of connection and healing within communities. Amber believes in the power of co-healing and helps people embody empowerment and explore the tools needed to self- and co-heal and move through trauma patterns that manifest as disease, sickness, white supremacy, disconnection, and mental imbalance.

The “I am a Vermont Artist” series explores how artists’ creative expressions reflect their experiences of ethnicity, gender identity, religion, disability, or age. Covering all artistic disciplines, and a range of backgrounds—from New Americans to the state’s first residents—we hope to amplify voices that deepen our understanding of what it means to be a Vermont artist. This story by the Vermont Arts Council originally appeared at

by accdWebMaster | Dec 2, 2021 | Communities, Northeast Kingdom, Quality of Life, Relocation, Vermonting

Was it COVID, climate change, or just a yearning to be free from big city life? Whatever the reason, there has been a resurgence of interest in living, working, and playing in northeastern Vermont, a region known locally as the “Northeast Kingdom”. And a leader in this exciting revival has been the historic hub of the Northeast Kingdom, the town of St. Johnsbury.

“More and more people are coming to visit and live in St. Johnsbury,” says Gillian Sewake, Director of the St. Johnsbury Chamber of Commerce. “They’re looking for a walkable town with amenities, that’s safe, and full of outdoor activities and cultural attractions. We’re less than three hours from Boston and a great destination for a weekend trip, or a permanent place to live.”

Visitors flock to the Northeast Kingdom in the summer for biking and in the winter for skiing. And the autumn features some of the prettiest and most photographed vistas in the country, with colorful foliage against a backdrop of rolling hills. All of this is centered in St. Johnsbury, a small town of 7,500 people with fascinating museums, a college-like independent high school, a vibrant performing arts scene, and magnificent late 19th-century architecture.

New restaurants, a high end bakery, craft breweries, and a distillery add to the many specialty shops in St. Johnsbury. A large independent bookstore, Boxcar & Caboose, is in the center of the downtown district, and the Maple Grove Farms of Vermont Maple Museum highlights why St. Johnsbury is called the “Maple Center of the World”.

Outstanding cultural institutions and architectural gems, including the Fairbanks Museum & Planetarium and the St. Johnsbury Athenaeum, line Main Street. The one-of-a-kind attraction, Dog Mountain—home of the Stephen Huneck Gallery and Dog Chapel—brings dog lovers from around the world to the bucolic 150-acre dog park. Catamount Film & Arts is the cultural center for the region, with a full schedule of world-class performances, independent film showings, exhibitions, and community art opportunities. The Lamoille Valley Rail Trail connects the downtown to outdoor recreation with a gently sloping 17-mile four-season path for bikers, nordic skiers, pedestrians, and snowmobiles.

The website DiscoverStJohnsbury.com tells the story of why “There’s Only One St. Johnsbury”. Says Sewake, “Not only is it literally true that there is just one town named St. Johnsbury in the world, the phrase also describes the concentration of unique attractions and opportunities here in town. We are thrilled to welcome visitors and support all of our new businesses. St. Johnsbury is bursting with vitality. It’s becoming a must-see town when visitors come to Vermont.” Visit the website to hear from residents about what makes the town so special, and to view weekend itineraries and a full calendar of events.

Since 2001, the St. Johnsbury Chamber of Commerce has stimulated and promoted the vitality of St. Johnsbury’s cultural, commercial, and community resources. As a Chamber of Commerce and a Designated Downtown organization, the organization combines the economic and commercial goals of a Chamber with the structure of a Designated Downtown organization. DiscoverStJohnsbury.com

Facebook: www.facebook.com/discoverstjohnsbury

Instagram: @discover_st.johnsbury

by accdWebMaster | Nov 9, 2021 | Construction, Forest Products

By Christine McGowan, Forest Products Program Director at Vermont Sustainable Jobs Fund | Photo by Erica Houskeeper, courtesy of the VSJF

Ten years ago this summer, Hurricane Irene tore through Vermont, leaving massive destruction and flooding in its wake. Among the hardest hit were mobile home parks, where many residents lost everything they owned—including the roof over their head. So, when Steve Davis, a community-minded Hartford builder with a long record of energy efficient construction, got a call from the Vermont Modular Housing Innovation Project, he didn’t hesitate to take on a ten-home pilot project to replace homes lost in Irene.

Davis and his team worked with state partners including Efficiency Vermont, the High Meadows Fund, and the Vermont Housing and Conservation Board to design an affordable, modular, net-zero home. Inspired by the models and convinced there was a broad market for the homes, Davis and his niece, Kristen Connors, founded VerMod, a modular home construction company with an emphasis on sustainability and affordability.

Over the past decade, VerMod has built more than 100 energy-efficient modular homes for Vermonters, improving on their model and adjusting to customer feedback along the way.

“There is a real need in Vermont for affordable housing,” said Connors. “As people downsize or maybe think about purchasing their first home, there is a lot of interest in energy efficient homes that use natural and low-VOC materials. They are healthier to live in and better for the planet.”

For Vermonters, by Vermonters

A sixth generation Vermonter from Hartford Village, Connors sees an opportunity to provide housing for low and middle-income Vermonters. Built with New England weather in mind, the company’s solar panels can be prepped to provide battery storage to ensure homes have power when the sun isn’t shining and in the case of power outages. Each VerMod roof is built to withstand Vermont’s snow levels, based upon the final destination of the home.

Energy efficiency requires the homes to be tight—especially during cold Vermont winters when we want to retain as much heat as possible—but they also need to “breathe” and bring in fresh air. The company uses a Conditioning Energy Recovery Ventilator (CERV) to continually monitor VOC’s, pollutants, carbon dioxide, and humidity to ensure healthy air quality.

“It’s a home that requires some education and commitment,” said Connors, who notes that they work with customers on an ongoing basis to ensure the home functions at its full potential. “We don’t just deliver a home and walk away; we stick with our customers for years to make sure they really understand how to maintain the home.”

While energy efficiency is their focus, VerMod is also careful to use materials and practices that reduce the company’s carbon footprint, and that includes using wood to construct the “good, solid bones of the house.”

“Steel is not our gig,” said Connors. “We live in a place where wood is abundant and we incorporate as much locally-sourced lumber as we can into our homes.” Steel manufacturing is both an energy- and water-intensive process, and a known contributor to global carbon emissions. According to the American Forest Foundation, the manufacturing of steel and concrete emits 15 and 29 percent more carbon dioxide than wood, and generates 300 and 225 percent more water pollutants, respectively. In addition, wood is a renewable resource that stores carbon when used in construction.

More practically, Connors says they like to work with people they know who stand by their product, and their customers like the warmth of wood in their homes. The company sources lumber for wood framing, flooring, and paneling locally from Goodro Lumber in Killington and Baker Lumber in Hartford. Connor’s own VerMod home was built using beams and hemlock siding milled from trees cleared on her property, and the additional timber was passed on to another VerMod homeowner.

The Future of Affordable Housing

Sustainability is not only the goal for each VerMod home, but for the company itself. Connors and Davis envision a scale of growth over the next decade that benefits and supports the Hartford community, and allows them to be creative with their designs. “We live in a tourist town that is filled with working-class people,” said Connors. “There is such a need for affordable housing in Vermont and we really believe our contribution and impact in the long-term is building those homes in a way that is healthier for people and the planet.”

The recently constructed Davis Towers in Hartford offer a glimpse into their vision—colorful, compact, and highly-efficient. “We want VerMod to benefit communities,” said Connors. “Single moms, hard-working middle class families, retired people on a fixed income looking to downsize their homes and carbon footprint—that’s our market. We want to have fun building these homes and, hopefully, leave behind a legacy of energy-efficient, affordable housing in our community.”

About the Vermont Forest Industry Network

Vermont’s forest products industry generates an annual economic output of $1.4 billion and supports 10,500 jobs in forestry, logging, processing, specialty woodworking, construction and wood heating. Forest-based recreation adds an additional $1.9 billion and 10,000 jobs to Vermont’s economy. The Vermont Forest Industry Network creates the space for industry professionals from across the entire supply chain and trade association partners throughout the state to build stronger relationships and collaboration throughout the industry, including helping to promote new and existing markets for Vermont wood products, from high-quality furniture to construction material to thermal biomass products such as chips and pellets. Learn more or join at www.vsjf.org.

Story originally appeared on the Vermont Sustainable Jobs Fund’s website: https://www.vsjf.org/2021/04/29/a-vermonters-approach-to-sustainable-affordable-housing/

by accdWebMaster | Nov 8, 2021 | Creative Economy

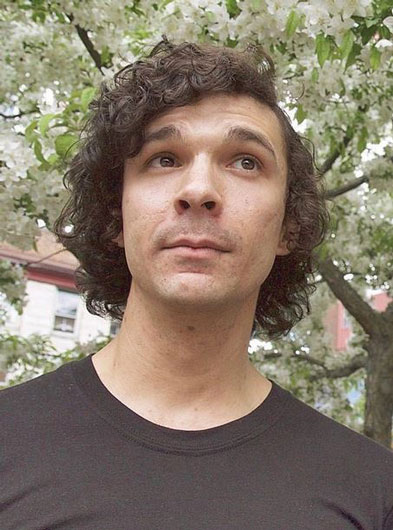

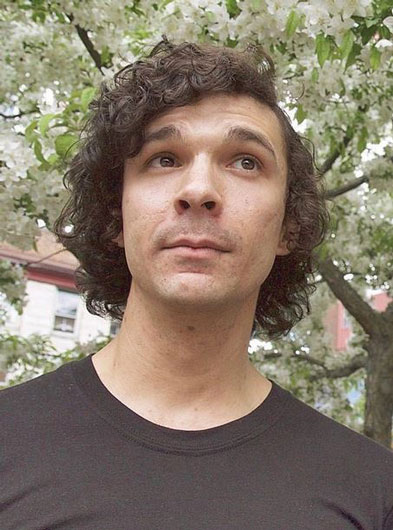

Desmond Peeples is passionate about the arts in rural communities. “When a small town’s artists and arts organizations are empowered and active, they enable neighbors, peers, and coworkers to meet in the strange spacetime of creativity and rediscover each other; they can help transform the way an entire community sees and feels itself.” One way Desmond is trying to accomplish these connections is through Mount Island, a literary magazine for rural LGBTQ and POC voices, for which they are the founding editor and editor in chief.

Desmond shares their thoughts about being an artist in Vermont.

How has living as an artist in Vermont affected your creative process?

The land has been a gift. A supreme presence whose spirit I’m lucky and challenged to be in conversation with. The solitude has always been a driving force, sometimes toward creative actualization and sometimes just toward loneliness. I’ve cherished the intimate sense of community here, but growing up as a queer, mixed-race Black Vermonter was a constant, often dogged, hunt for respect and solidarity, and for intimacy with others like me. Making art has always been a tool in that hunt, whether for soothing the spirit, interrogating truth, or reaching into community.

Since returning to Vermont after some years bouncing around the country, I’ve realized how essential community is to my creative process. With the help of countless other artists who feel similarly, I’ve been learning how to better ground myself in community where it exists, and to create it where it’s needed. It’s an ongoing struggle, but it—like Vermont—means the world, means home to me.

What is something about your art that has changed over time?

For years the ethical substance of art was my primary concern, but now style is equally important to me. I’ve become obsessed with how style and substance can work together, in service to each other’s reckoning with the human experience.

What is your vision for the next several years?

I’ve been working on two novels I’d like to see published, both set in the Enlightenment era. One’s a punky look at queer lives back then, the other an alt-history fantasy about a pagan nation’s invasion of Europe.

I’d also like to devote more energy to making music. I’ve been mulling over a folky, bluesy album for a while. And I’m itching to return to singing in drag—that’s an irreplaceable feeling I miss.

Then there’s running Mount Island, the first issue of which comes out this October. Our long-term vision is a sustainable publishing house grounded in equitable community-building.

Visit Desmond’s website.

Take a look at Mount Island’s website.

Read an interview with Desmond in the Brattleboro Reformer.

The “I am a Vermont Artist” series explores how artists’ creative expressions reflect their experiences of ethnicity, gender identity, religion, disability, or age. Covering all artistic disciplines, and a range of backgrounds—from New Americans to the state’s first residents—we hope to amplify voices that deepen our understanding of what it means to be a Vermont artist. This story by the Vermont Arts Council originally appeared at https://www.vermontartscouncil.org/blog/i-am-a-vermont-artist-desmond-peeples/